Continuing our series on the office market & NYC in particular, I want to spend a little time on the much hyped subject of conversions. It has garnered a fair number of headlines but the analysis is all pretty superficial so I wanted to spend a bit of time doing a deeper dive. First I should make clear that I have never done an office to residential conversion myself, but I am a developer and have experience in both owning office buildings and building apartments. So what I present here is based on my knowledge of both asset classes, and things I’ve learned investigating conversion projects other folks in CRE are doing. In other words - I think this is reasonably accurate but I may miss a few (hopefully small) things here or there. If I do please call me out on it!

The ability to convert office space into residential is one of the things that makes NYC’s office market unique1 – it gives the market an additional mechanism to remove supply. This mechanism would help insulate the NYC market in a worst case demand decline scenario by taking supply offline. This isn’t just speculation - office to residential conversions are happening right now even at today’s pricing, and previously happened at fairly large scale in the 1990s, 2000s and even 2010s.

1 West Street - a 492 unit conversion in downtown Manhattan completed in 2001

All that said - converting an office to residential is very expensive even in a best case scenario – so much so that in most office markets it really doesn’t make any sense to do so. To make the math work you need really strong land values, and offices in locations where people actually want to live and will pay premium prices. Manhattan is one of the few places in the country where you have both those elements in the same place and in fact the market has a long history of these projects. This contrasts to most struggling suburban office markets where the cost to convert is so high relative to the land values that it makes more sense to just scrape the office buildings.

I want to dig into the conversion topic a bit, as first off all its just plain interesting, and secondly it’s an important mitigant for a worst case WFH scenario. I admit it is difficult to predict where the final impact of WFH will shake out, although again as I laid out in part 1 the data seems to indicate we’ve seen most of the impact already while what’s being priced in is another massive decline.

Why conversions are hard

First – why are office conversions so difficult and costly? A few main reasons. The first is just that a lot of the cost in a residential project is building out the actual apartments, with all the individual work per unit related to plumbing, electrical, fixtures etc. A conversion doesn’t save on any of this. Another is the large floor plates offices often have, in particular the depth (or furthest distance from a window). This is problematic because most cities require windows in bedrooms. Bedroom windows mean the bedrooms are all along the outer walls, and the unit must run from the access corridor to the exterior wall. This means in a deep floor plate building the living / kitchen space can feels like a huge cave with no light as a wider floorplate necessitates units have a relatively long depth and shorter width. This also means that units are relatively larger, as each unit is much deeper than an equivalent custom built unit. Rent per square foot scales down with unit size (particularly for awkwardly laid out units), so these larger units are also worth less per square foot than smaller units.

Another thing you may have noticed from the crude drawings is the difficulty posed by a large floor plate office building whose elevator core is side loaded. These can be even less efficient.

Again even this problem can be fixed at a sufficiently low enough basis (amenity space in the middle of each floor, eating the dead hallway space, or just enormous units with correspondingly lower PSF values), but realistically this rules out a lot of potential buildings from being converted unless prices got really cheap.

Another issue is that offices and apartments measure & rent available square footage differently. Office tenants essentially pay rent on the entire building square footage, including common areas, where in an apartment you don’t. The difference is mostly academic, but it matters in a conversion, because your net rentable square footage for residential is smaller than for office on a given building. The loss factor is typically somewhere around 20%, ranging up to 25% or more depending on how big the amenity package is etc. So this means the effective price paid PSF is higher for the residential than the office. For example an office building bought for $300 psf, would yield a residential basis of ~$375 psf.

Finally - as a rule multi-tenant buildings can be hard to convert as the leases of the tenants do not often line up well in terms of their expirations. So a building may be say 25% leased, but the final tenant could have several years of lease term left which would preclude converting the project until they leave. This could be accomplished via a lease buyout, or otherwise the owner would have to wait until the lease expires. The pool of buyers for a building that is several years out from being able to start a conversion is going to be much smaller than one which is fully vacant and ready to go.

Zoning & Regulation

Zoning is the other big barrier. In most cities the zoning (either through use, FAR or code compliance) is flat out incompatible with conversions.

However NYC already has a fairly permissive office to residential zoning regime relative to almost every other metro area. Office to residential conversions are already allowed in essentially all of Manhattan’s major office districts.

The above map from the city details the current conversion regime (link here). For our purposes the most important thing to understand is that the light green and blue allow conversions. This covers all of the financial district plus the major midtown office districts.

Its not entirely carte blanche though - the conversion rules are different depending on the building age. Light green allows for more flexible conversion for buildings built before 1961, and the blue is before 1977. However there is a separate provision which limits FAR on conversions to multifamily to 12 for buildings built after 1968, so this is limiting for certain FiDi buildings.

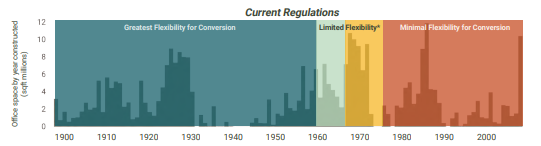

Obviously it would be better if more recent buildings were allowed, but there are actually quite a large number of buildings built before 1961 (or 1977 in FiDi). Here is a chart showing NYC’s office stock by year built. Much of it was built post 1961, but a very large fraction is pre 1961. The city doesn’t provide an exact breakdown of stock by year and I haven’t run a full analysis myself, but for our purposes there is more that enough office available for conversion under the current regime - just eye balling it it looks like at least 75-100mm sf.

Many of the conversions utilized various city tax break programs, most notably 421-G (which expired back in 2006 as the office market had regained its strength).

Despite these hurdles, in NYC land values and residential demand are high enough to actually make the math work here, and the zoning does allow for it in a decent number of buildings. Also the older buildings currently covered typically have smaller floor plates that are more suitable for conversion, so many of the prime conversion candidates are already covered under current regulations ( office floor plates grew over time up to around the 60s and 70s, so buildings built before those decades typically have smaller floor plates).

Potential NYC conversions in context

To give some sense of scale on potential demand for conversions vs current office stock here is some quick math. Manhattan has roughly 475 million square feet of office space. Converting 5% of that space would be 23.75 million square feet. At 80% efficiency & a 650 square foot average unit size that’s just under 30k units. More likely these are larger units (hard to do small units in conversions per the above) - to give a range at around 1k sf , it would be more like 19k units.

That may seem like a huge number, but the New York multifamily market currently has 65,000 units under construction right now. Yearly absorption is 20-30k/year. This is a city with nearly 8.5 million people and a metro area of 20+ million. 20-30k units is ultimately a drop in the bucket.

And contrary to what many people might believe who don’t live here or come here often, but the NYC multifamily market is very strong from a demand perspective. Even the traditional office markets of midtown and the financial district have strong residential demand with numerous residential buildings already there.

So – you could easily convert 5% of Manhattan’s office stock, or hell even 10%, from a pure demand perspective. I don’t think that actually happens, but in a downside scenario where vacancy stays high for years I believe it could. This mechanism will serve to normalize supply and demand in office over the longer run in a worst case WFH scenario, and even is occurring today with current market conditions. At today’s 18%2 vacancy rate, 5% brings you down to a very healthy 13% vacancy, which is where we were pre-covid. Now I highly doubt that much conversion gets done (at least in the next 5 years - on a longer time frame it may well) – I don’t think the market will need it. But in a worst case scenario (which is already priced in) it could happen.

History

A bit of history may also be helpful – this is not the first time Manhattan office space has struggled with high vacancy. The NYC office market suffered a terrible bust in the early 1990s due to massive overbuilding combined with recessionary job losses. In response to this glut of space the city enacted some of its first measures to allow conversions of office to residential.

Right as the market had finally recovered, the dotcom bust followed by 9/11 hit high rise office demand, especially in lower Manhattan. No one wanted to lease space in what was then viewed as potential terrorist targets.

So what happened? A wave of office to residential conversions occurred beginning in the 1990s, with over 20 million square feet of office space converted to residential in the Financial District. And of course over time corporate behavior normalized, and the aversion to high profile high rises went away.

The conversions continued after the financial crisis - from 2010 to 2020, ~10 million square feet of offices were converted to residential or hotel! Here is a summary, straight from the city’s recent task force report on office to residential conversions (link here).

Some of the conversions in the chart above is double counted in the 20mm FiDi number - so I estimate 23-25mm sf total have been converted since 1996. That is ~5% of the Manhattan office inventory! To some people this may seem like a small number, but in real estate 5% is huge. In a world where 16-18% is high vacancy, a 5% reduction in supply is enough to push a market from soft to strong. Of course this played out over 20+ years, but the main point is that in each downturn & recovery cycle office conversions played a meaningful role in reducing total market vacancy in NYC.

New Conversion Incentive

Coming back to the present - conditions appear to be set for a new wave of conversions. The city government is actively working on ways to encourage more office conversions, and in fact just the other day announced a critical new tax incentive program to support office to residential conversions.

The program is called M-Core, and is designed to support up to 10 million square feet of conversions. From what I can tell the program stabilizes existing tax values and offers a 20 year property tax abatement (which burns off linearly during the last 4 years) on office to residential conversion projects for buildings built before 2000 and located below 59th street (so basically any building you’d want to convert).

This abatement is a pretty big deal. Property taxes in NYC are (no surprise) very high. They can be over $30 psf for nice buildings. For some simple math if you assume the existing building was taxed at $10 psf, but would have increased to $30 post conversion that’s an abatement savings of $20 psf / year, for 18 years (after accounting for the phase out). At a 6% discount rate that is ~$215 PSF in present value. For a building that might have a total basis of $800 psf this tax break is a huge benefit.

I would expect at those kind of numbers that all 10 million square feet of this program get utilized, which would reduce Manhattan’s vacancy rate a full 2%! This would be a really meaningful boost, meaning only ~3% of the market would need to be leased from demand to bring us back to 13% vacancy. I’ll come back to the subject of potential market growth in more depth in the next article, but at 175 sf / job NYC would need around 81,429 new office using jobs to recover 3% vacancy (475mm sf * 3% /175).3 That may seem like a lot, but the NY metro has around 2.7 mm office using jobs today, and added about 267.5k from 2013-2019. Assuming Manhattan has an outsized capture rate for office jobs, NYC needs only a fraction of the last cycle’s growth to hit 3%.

Conversion math

Digging in a little more on the math behind conversions – if the stock market really is right and stabilized class A buildings are worth ~$300 psf, that would imply empty C buildings are worth under $150 psf, definitely cheap enough to make conversion math work. For context today people start to consider conversions at basis below $400 psf, if the building lines up well in terms of floor plates, elevator core position etc.4

At $150 psf the math can work even for buildings that are weaker conversion targets, and you could make conversions work en masse without the bedroom window rule being changed by cutting interior courtyards into buildings (this has been done downtown before believe it or not! This appears to begin to be feasible around $200 psf to the building for context). A prominent current example of this is 25 Water Street, a conversion currently underway of a massive old 1.1 million square foot office building into 1,300 apartments which involves cutting two separate courtyards into the building. This building was D quality, as it was built to house telecom equipment and had extremely limited windows – the developer is re-skinning the exterior to provide larger windows, a very expensive endeavor.

Again a little more context for non NYC folks – new residential buildings are easily worth north of $1k psf here. So if you can buy for $150 psf, that would be $187.5 psf to the resi (given our 20% loss), spend $450-500 converting, then sell for $1.1k…. the returns are pretty good, it’s a 60%+ development margin. The normal math is more like $350 psf on the buy (which turns into more like $440 psf net to the residential due to loss factors), spend $450-500 converting, then sell for $1.1k. Development margins in real estate for apartments are usually 20-30% for context (build for $100, sell for $120-130). For sub-optimal buildings your conversion costs go up and/or basis is higher as you need to lose more square footage for light/window rules.

So if REIT implied values really were correct, then you would see a massive wave of office to residential conversions as the REIT pricing implies many buildings would sell for sub $150 psf. Which of course would take a large amount of office space offline. But I just don’t see this happening - the conversion math gets too juicy and a bunch of developers would jump on the opportunity and bid up pricing. Still - I do think private values will likely fall a bit further before we are done, but nowhere near what current stock prices imply.5

As a caveat though – even in a base case, it would take 1-3 years for conversions to take a meaningful amount of space off the table. Buildings become available and sell at a slow clip in downturns. Luckily while the construction may take 2-3 years, what matters to the office market is when space is no longer available for lease, which pretty much happens once a building sells to the conversion developer.

In Sum:

Conversions are costly & difficult, and only really make sense in a handful of markets. Manhattan is the best market in the country for conversions by a mile due to its strong residential values, high land prices, & (relatively) favorable zoning regime.6 Even so, conversions will likely only end up taking a few percent of inventory off the market. But in CRE a few percent goes a long way, and this safety valve should mitigate any worst case downside demand scenarios.

Coming back to the overall NYC office market and the REITs, conversions are already starting to help, but will take a few years to ramp up. So I don’t think the current market softness is going to end anytime soon in the NYC market. And in a true worst case WFH scenario the NYC office market could languish for several years. However at current prices you are being amply compensated to wait, and over a 5 year hold period the returns look very attractive. I’ll dive into just how good in my next article.

To be precise there are a few conversions in most historic downtowns across the country at this point, so what I really mean is that NYC is one of the only markets in which conversions can happen at a large enough scale to actually influence the overall market.

You may recall that I showed the NYC vacancy rate as 16% in my prior article. That is based on Costar data, which allows for a clean apples to apples comparison across cities. Commercial brokers also produce market data & reports, and if you average the major brokers with Costar the vacancy is more like 18% (trendline is basically the same). So for underwriting I use the higher 18%, hence the difference. But I don’t like using broker reports across markets as each market operates a bit like a pod, and each market produces their own reports and there is significant quality variability across a given brokerage city to city. EG broker X may be strong in office in NYC but have a very weak DFW office team. So you can’t really just use broker X’s data across the country. Whereas Costar is a data platform so you get much more consistent data across the country.

Total growth needed will actually be a bit higher than that as there is some new supply still under construction.

Price can go even higher than this on a conversion use for the right asset - for example the Flatiron building just sold for $161mm at auction, which is about $630 psf. The plan apparently is to convert the building to condos. This building is a strong candidate - small floorplates, old, it is located right next to a park, and is famous to boot.

If I had to guess I think we’ll see some Fidi B/C buildings trade in the mid to upper $200s psf - the loan sale of 61 Broadway will be a good value benchmark. Fidi generally has lower rents and higher vacancy than midtown as it is further from the major train stations & the buildings are typically older and lower quality. This is why it has been the epicenter for conversions.

There is still a lot more the city could do in terms of loosening restrictions on conversions of buildings built in the 60s, 70s, & 80s - all of which is actively under discussion and hopefully gets done.